Robert Russell, Melbourne from the falls, 30 June 1837

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Learning about First Nations history, culture and knowledge.

In and around the Yarra Valley, for over 60,000 years, the Wurundjeri people have lived sustainably. They identify as the "Manna Gum people" because of their deep connection to this tree from which their name is derived from 'wurun' (Manna Gum) and 'djeri' (the grub found in the tree).

The Wurundjeri have important Creation stories that feature the creator spirits who shaped the land, who helped create the first humans from the bark of a manna gum tree and who established the laws of the land.

Their society was governed by complex systems of law and kinship, and they passed down knowledge, traditions, and creation stories through oral traditions, art, song, and dance.

Colonisation effectively destroyed this civilization. In the Yarra Valley, we have two important stories. In 1840, the famous Battle of Yering occurred and in 1863, Coranderrk was created as a place for the few remnants of different mobs who survived the early expansion of Melbourne.

John Cotton, Aboriginal camp on the banks of the Yarra, c.1845

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The woman shown here wears a possum-skin cloak. About eighteen skins were needed to make a cloak.

Yesterday

Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung

The Wurundjeri are the Traditional Owners of the Yarra River region, part of the Woi-wurrung language group of the Kulin Nation. Their identity is tied to Birrarung and the land. Society centred on clans with spirituality shaped by creation stories.

Creation stories

Bunjil

Bunjil, the wedge-tailed eagle, is believed to have shaped the land, rivers, and living beings, giving the Wurundjeri their laws and responsibility to care for Country. Supported in some stories by his wife Ganawarra and brother Mindi the snake, he later ascends to the sky as a star watching over all.

Moorool

Wurundjeri Elders Barwool and Yan-yan cut channels to release the great waters Moorool and Morang, which joined to form Moo-rool-bark and created the Yarra River. Their efforts opened a path where waters rushed out to form Port Phillip Bay. Archaelogists suggest this story may reflect post–ice age flooding when the seas rose and flooded this bay.

Birrarung

Birrarung, or the Yarra River is an important Aboriginal cultural landscape with deep spiritual significance for the Wurundjeri people, serving as a life source and meeting place. For many locals, it remains a place of cherished memories, from peaceful summer evenings to personal journeys and days spent exploring its banks.

Complex and diverse societies

Before European contact, Aboriginal peoples lived in complex and diverse societies.

Diverse Nations:

Australia was home to hundreds of distinct nations and language groups, with complex kinship systems and rules for social interaction.

Hunter-Gatherer-Fisher:

The primary way of life was hunting and gathering, with people moving across their country in accordance with the seasons.

Sustainable Resource Management:

Communities harvested only what they needed to ensure resources were maintained for the future, a practice that supported sustainable living and prevented depletion.

Connection to Land:

There was a deep, spiritual connection to the land, which provided all the resources needed for survival.

Culture and spirituality

Rich Cultural Life:

Abundant leisure time allowed for a rich and complex ritual life, including ceremonies, dances, and the creation of objects that bound the physical, spiritual, and human realms.

The Dreaming:

The Dreaming played a central role in their worldview, representing a complex cosmology of spirit beings who provided the blueprint for life and were connected to the creation of the world.

Language and Law:

Each nation had its own unique language, and a complex set of laws guided social interactions, education, and spiritual development.

Social structure

Egalitarian Society:

The social structure was relatively egalitarian, with age, gender, and land affiliations being important factors.

Kinship Obligations:

Strong kinship obligations dictated responsibilities to family and community, ensuring that children were nurtured and protected.

Corroborees:

Annual gatherings called corroborees brought different groups together for trading, arranging marriages, and performing ceremonies, which strengthened social and cultural bonds.

Six seasons of Wurundjeri

The six Wurundjeri seasons are based on observations of the weather, plants, and animals. They are Biderap (Dry Season, Jan-Feb), Iuk (Eel Season, March), Waring (Wombat Season, April-July), Guling (Orchid Season, Aug), Poorneet (Tadpole Season, Sept-Oct), Buarth Gurru (Grass Flowering Season, Nov), and Garrawang (Kangaroo-Apple Season, Dec). These seasons are based on observations of the weather, plants, and animals.

Six layers of country

The six layers of Wurundjeri Country are Biik-ut (Below Country), Biik-dui (On Country), Baanj Biik (Water Country), Murnmut Biik (Wind Country), Wurru wurru Biik (Sky Country), and Tharangalk Biik (Star/Bunjil's Home Country). These layers are intrinsically connected, representing a holistic view of the land, culture, and spiritual beliefs that are essential for the wellbeing of the Wurundjeri people.

Melbourne before settlement

This interactive map reveals something of Aboriginal peoples’ deep connection to country prior to European settlement and significant events and experiences since colonisation.

Colonization - the Battle of Yering

The Battle of Yering occurred in early January 1840. This confrontation was a major event in the Wurundjeri resistance to the takeover of their lands and it started in Warrandyte. Jaga Jaga (also known as Jika Jika or Jackie Jackie) and a group of Wurundjeri stopped at Anderson’s Run on their way upriver. James Anderson had established his run at the confluence of the creek known as Bie-el Yallock (Andersons Creek) and the Yarra River.

Settler Anderson had planted out potatoes in the loop of the river now known as Pound Bend and the Wurundjeri proceeded to dig up some of these ‘white man’s yams’ with their digging sticks. When Anderson discovered what he considered to be theft, he went to their camp and proceeded to harangue and threaten them with arrest. However the Wurundjeri were in possession of some muskets given to them by the Chief Protector of Aborigines (apparently to obtain the tail feathers of the Lyrebird for him as these were in much demand). A shot was fired which zipped past Anderson’s ear and he wisely withdrew amid more warning shots. Angry, he lodged a deposition on the 7th of January requesting action be taken.

In response, Henry Fyshe Gisborne, Commissioner of Crown Lands in the Port Phillip District, set out with three troopers to apprehend Jaga Jaga and seize the firearms. The Wurundjeri men had meanwhile continued to Yering Station further upriver and Gisborne, arriving before them on the 13th January, devised the stratagem that the station owner should kill a bullock and invite the Wurundjeri to the feast. It took several men to capture Jaga Jaga, a well built and powerful man. As other Wurundjeri rushed to his aid, they were deterred by Gisborne drawing his pistol and threatening to shoot.

Jaga Jaga was secured by rope and put in a hut watched over by servants. The remainder of the Wurundjeri strategically retreated leading the troopers into the bush and eventually withdrew into a swamp where horses could not follow. Meanwhile Jaga Jaga succeeded in making good his escape and no arrest was made.

Source: Warrandyte Historical Society

Coranderrk Station, State Library of Victoria

Coranderrk

Since the beginning, our Ancestors cared for Country on which present-day Coranderrk now stands. Colonisation caused great disruption to Culture and Country and, despite ongoing resistance and attempts to reclaim their lands, our Ancestors were pushed to the outskirts of the new settlements.

In 1863, our Ancestors found refuge at Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, at the confluence of Birrarung and Coranderrk creek. The many who lived at Coranderrk, worked hard to build an autonomous farming community, where other displaced mobs could coexist. The size of Coranderrk changed many times, and at its largest covered some 4,750 acres.

Source: Coranderrk Strategic Plan.

Coranderrk and Healesville – a shared history

Fifteen posters Fifteen posters developed by Nicola Stairmand provide a fascinating insight into life and times at Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, the many enterprises carried out by our ancestors and the strong links they forged with the community of Healesville including the Coranderrk school and sport.

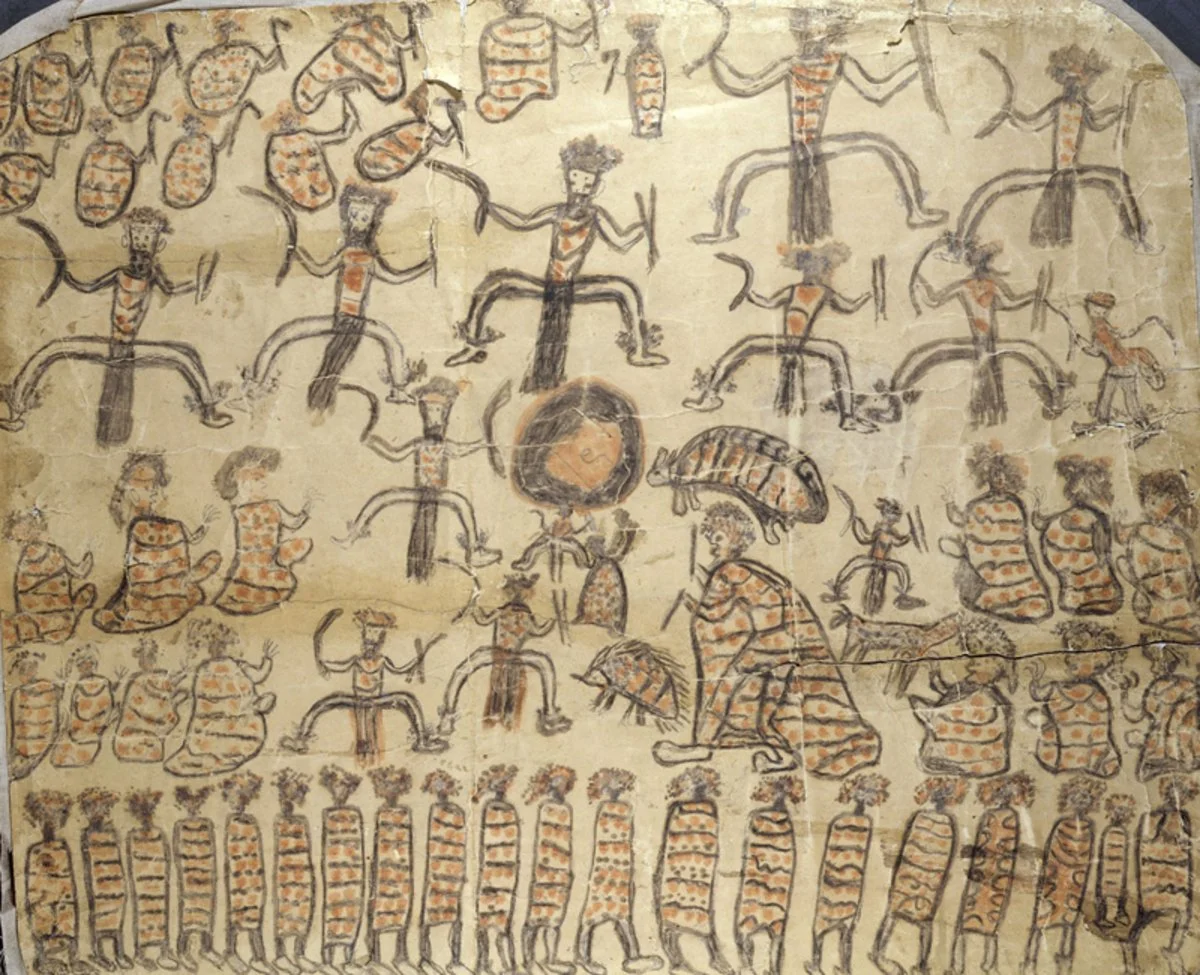

Illustration by Barak. Victorian Collections

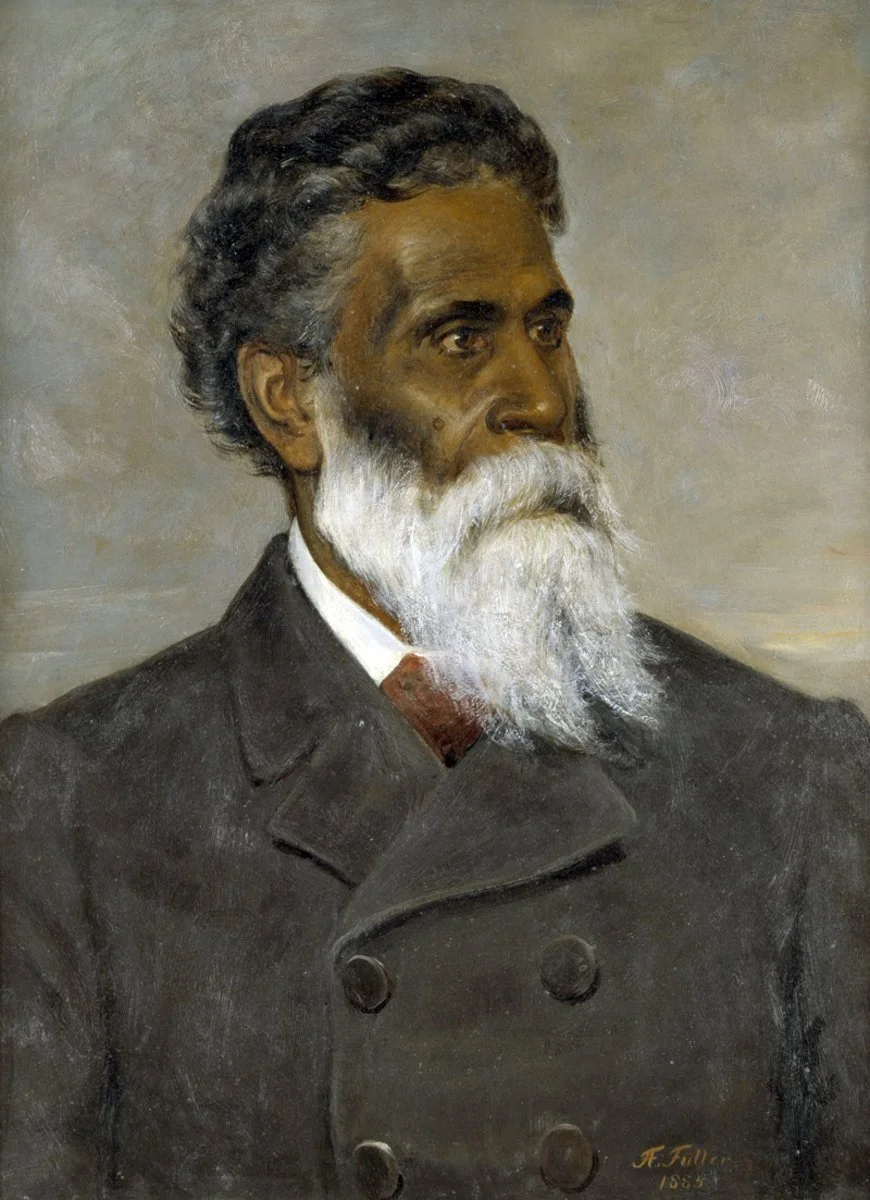

Barak

William Barak was born in 1824 to Bebejan, a Ngurungaeta, and Tooterie at Brushy Creek in the Yarra Valley, now known as Wonga Park. Uncle Barak spent most of his life at Coranderrk and was devoted to its cause. He was known as a man who was highly intelligent, charismatic and mild mannered.

Barak was a skilled artist, creating many paintings reflecting his Wurundjeri culture while at Coranderrk. Barak was a strong leader and advocate for his people – often successfully negotiating and building relationships between Wurundjeri people and Europeans.

Barak succeeded his cousin Uncle Simon Wonga as Ngurungaeta of the clan in 1875 and his diplomacy earned him genuine respect and support from white colonists.

After becoming Ngurungaeta, his leadership was put to the test when Coranderrk came under threat of closure. The Protection Board was under pressure to subdivide the land and shift residents away from their homes to a remote spot on the Murray River. This was strongly opposed by the residents of Coranderrk. Barak also led a large group of people on a walk to Parliament House – recreating a walk he had previously done with his cousin, Simon Wonga, when they had sought permission to establish Coranderrk.

In the meeting at Parliament, Barak was able to convince the Government not to shut Coranderrk down. This shows that Barak was able to adopt peaceful yet persuasive ways to fight for Country.

In 1881 Barak organised a third walk to Melbourne after Coranderrk was once again being threatened. He led 22 men along the 60km journey from Coranderrk to Parliament House. The Parliamentary Inquiry into Coranderrk was the first time in Victoria that an official commission was created to address Aboriginal people’s calls for self-determination and land.

Barak sadly passed away in 1903 but his legacy lives on.

Source: Deadlystory.com

Coranderrk today. Wandoon Estate Aboriginal Corporation

Today

Today, our knowledge or more accurately our lack of knowledge about indigenous life before European settlement and the truth about the impact of colonisation is recognised as the most significant barriers to reconciliation.

Our first step is to start learning. Indigenous knowledge and land/water management practices are starting to make a huge contribution to our adapting to climate change.

First Nation’s people from the Yarra Valley are today, some of Victoria’s most important indigenous leaders including Auntie Joy Murphy, Dave Wandin in cultural burning and land management, Brooke Wandin in regenerating Woi Wurrung language, Kim Wandin and Jacqui Wandin as artists.

Adapting to climate change

It is now widely accepted that we need to change our land management and our water management practices to adapt to the changing climate. Ironically, our best teachers are the First Nations people who have lived in partnership with the land, water, plants, animals, insects etc for over 60,000 years. They call this caring for country.

Combining ancient wisdom with modern science

The First Knowledges series of books provides an understanding of the expertise, wisdom and ingenuity of Indigenous Australians in a broad range of areas including health, law, design & building, astronomy and plants and their application to the present challenges.

The books bring together two very different ways of understanding the natural world: one ancient, the other modern.

Cultural burning

Indigenous cultural burning is a 60,000-year-old land management practice using low-intensity, controlled fires to reduce fuel loads, prevent large bushfires, and promote new growth. Conducted seasonally and with cultural significance, these “cool burns” create diverse habitats, support native wildlife, and maintain healthy, resilient ecosystems across the landscape.

Aboriginal Cultural burning at Coranderrk Station Wurundjeri ABC News

Smoking Ceremony Yarra Ranges Council

Coranderrk wakes up from a long sleep

Coranderrk remains a powerful symbol of Aboriginal resilience and continues to help us address critical challenges. It is a safe place for people to connect with each other, the land, and Aboriginal culture. Today it embodies reconciliation and demonstrates how Aboriginal knowledge supports climate action and sustainability, echoing Elder Dave Wandin’s message: “Heal Country, heal ourselves.”

The Statewide Treaty Bill in Victoria - a treaty with Traditional Owners

Victoria's first treaty with Aboriginal people has been recently signed by members of the Aboriginal community, the premier and state governor. The treaty …"brings together the First Peoples of these lands and waters — through the First Peoples' Assembly of Victoria — and the State of Victoria on behalf of all Victorians, to forge a renewed and enduring relationship built on respect, trust, accountability and integrity”.

Coranderrk today. Wandoon Estate Aboriginal Corporation

Indigenous Culture

Local indigenous artists

Indigenous culture is something we are starting to learn about and to appreciate. Today we are lucky to enjoy the works of many Aboriginal artists, musicians, designers, writers and storytellers. Importantly, there is a new generation of First Nations cultural workers proudly emerging.

Locally, some of our local First Nations people are among Victoria’s established and emerging cultural leaders.

Jacqui Wandin – Artist, Education

Art, Education

Brooke Wandin – Artist, Education

Aboriginal Perspectives in the Class Room

Major new public art work champions woiwurrung language

Kim Wandin - Artist, Author

Triennial Artist Designer Kim Wandin National Gallery of Victoria

Metro Tunnel Community Art

Nets Victoria

Aunty Joy Murphy – Elder, educator, author, activist

Storm Controversy

Untitled Seven Monuments, Untitled Seven Monuments

NGV Contribution

Awards

Looking towards Healesville from the river flats. Wandoon Estate Aboriginal Corporation

Tomorrow

One day at Coranderrk recently, when asked about what they wanted us (non-indigenous) people to do, we were offered three simple responses. Dave Wandin’s advice was “when walking in the bush, stop for a moment and use all your senses - look, listen, smell, taste, touch.” In other words, start to actually observe what is happening around you and to try to learn. Brooke Wandin, remembering when she was at school, she was taught nothing about Aboriginal history that we should learn about our heritage, about life in Australia before 1788 and the truth about the impact of colonisation. Jacqui Wandin said to “reach out, we are waiting with love in our hearts to start walking and working together.

There are lots of easily accessible online resources and we provide some links below. A good start is to visit the Healesville Sanctuary for the Wurundjeri Walk. Do you want to do something practical to connect and contribute? Perhaps join your local Landcare group or become a Friend of Coranderrk. Alternatively, consider becoming a supporter of ‘Pay the rent’ program which is managed by a First Nations collective.

Do you want to learn more? Getting started

Two simple ideas. Step outside into your garden, local park etc and stop for a moment and use all your senses – look all around you, listen to the birds, can you smell anything, touch the leaves. Identify what country you are living or working on. What is the local language group? Perhaps acknowledge this in your communications.

Other ideas to get started are to:

Identify and make contact with the local or nearest Traditional Owner group.

Find out if there are any mountains, rivers, town that have Aboriginal names.

Contact your Council to see if First Nations history and culture is on display in your town. In the Yarra Valley, visit the Healesville Sanctuary.

Contact your local historical society about knowledge of local Aboriginal life before 1788.

Learn about the impact of settlement on Aboriginal people living in your area.

Identify the trees, shrubs and grasses that are indigenous to your area

Find the local indigenous seasonal calendar that observes the changes throughout the seasons. A great children’s activity is to prepare your own seasonal calendar.

Start to read novels by Aboriginal writers, listen to First Nations musicians, check out the new young clothes designers, the art exhibitions etc.

Volunteering - from talking to doing something practical

Join an existing group of volunteers to help make a bigger difference. Perhaps join the local Landcare group supporting sustainable land, water and biodiversity management. Join a Friends of groups such as the Friends of Merri Creek to take part in planting and site maintenance, bird surveys, water quality testing and litter blitzes. Join Friends of Coranderrk to help out at the monthly working bees. It is all ‘Caring for Country’.

Support Pay the Rent Program

Pay The Rent offers all Australians an opportunity to work outside of government to right the wrongs. Paying the Rent is about non-Indigenous people honouring the Sovereignty of Aboriginal people; it is a somewhat more just way of living on this stolen land.